How Central Bank Digital Currencies Will Forever Change the Payments Industry

Visa, Mastercard, and the Big 4 Banks are all at risk

We’re at the precipice of a major inflection point in payments and financial markets. Many central banks, including the Reserve Bank of Australia, are considering launching digital currencies.

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) have the potential to completely disrupt incumbents in the payments industry, permanently alter the composition of central bank balance sheets, and undermine existing banking business models.

In this article, I share some early thoughts on how CBDCs might affect the payments landscape in Australia.

What is money anyway?

Let’s start at the beginning. Without going too deep into boring economic theory, there is a formal definition of money. Money is something that provides a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account. In other words, it can be transferred, stored and measured.

For most of us, money comes in two forms. The first form is physical money or cash. Cash can be held by anybody and whoever holds the instrument is considered to own it. When somebody passes cash to another person, an exchange has occurred and ownership has been transferred.

The second form is digital deposits in a bank account. In many respects, it shares the definition of money above. However, electronic deposits in a bank account differ from cash in one key respect: electronic deposits are not legal tender and do not sit on the balance sheet of the Reserve Bank.

Instead, they sit on the balance sheet of the commercial bank as a commitment to give you legal tender when you ask for it. Usually, the bank has no issues fulfilling that promise. But as a deposit-holder, you take on a small degree of credit risk in the case of the bank failing.

What is a CBDC?

A CBDC is a digital form of currency that is similar to bank deposits. But importantly, it would be issued by the Reserve Bank as a form of legal tender and the liability would sit on their balance sheet.

The real innovation is in the design. The CBDC would most likely borrow new technological developments from the cryptocurrency space, such as the distributed ledger. In this article, I’m not going to dive into the technical detail of the CBDC. If you’re interested in understanding the underlying technology, I suggest you check out this paper by the Brookings Institution.

But it is worth looking at a couple of the major design decisions for the CBDC. These design decisions have a direct impact on how the CBDC will look and feel in the real world, and therefore how it affects existing payments systems.

Centralised or distributed CBDC ledger

Perhaps the most important component of the CBDC is the ledger. The ledger is effectively a proof of ownership that validates that “yes, you own these funds and can use them”. An Australian CBDC ledger could either be maintained by the Reserve Bank or in some form of distributed ledger (a la Bitcoin).

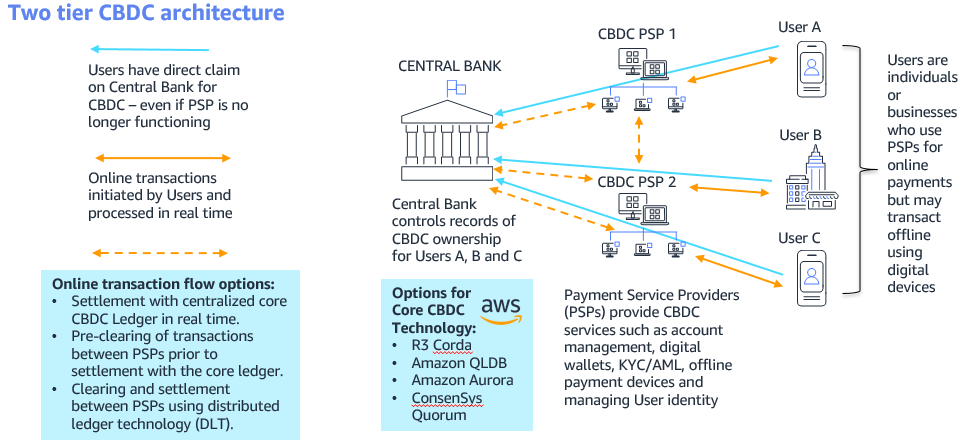

Either way, it most likely that the Reserve Bank would utilise a two-tiered model. They would be responsible for maintaining (or at least regulating) the CBDC ledger, and payment service providers (e.g. banks, fintechs, technology companies) would be responsible for consumer access and other customer-facing activities.

These customer-facing activities would include things like customer onboarding, KYC and AML/CTF checks, account keeping services, and transacting in and out of the CBDC.

Account or token-based design

An account-based CBDC design has much in common with today’s bank accounts and credit card accounts. The ledger would keep a record of every individual’s CBDC account balances. Before commencing a transaction, the system would have to verify that the account has sufficient balance to make the transactions. In many ways, this model is the equivalent of giving every Australian an account with the Reserve Bank

In contrast, a token-based design has much in common with cash. The Reserve Bank would issue a ‘digital token’ and the holder of that token is considered to be the owner of the asset. Before commencing a transaction, the system would simply have to verify the authenticity of the token.

What are the implications of a CBDC?

Traditional payment plumbing is hit hard

The ability to move money without friction would affect every card scheme, acquirer, and payment service provider in Australia.

Think about the parties involved in a credit card transaction... When you swipe your credit card in a store, the transaction is routed through the eftpos terminal, card gateway, switch, acquirer, card scheme, issuer… and then back. There’s plenty of profit in friction, and all of these parties take a clip of the transaction. That’s why merchants fork out 0.50-1.50% in fees per transaction.

To be fair, today’s payments infrastructure evolved organically, not by divine creator. Behind every payment, there is a complex web of connections between the millions of in-store and electronic points of sale, and the thousands of financial institutions that fund them.

But a CBDC model employs a much simpler design. In a two-tiered CBDC model, there is a centrally-managed or distributed ledger. Payments would be initiated by simply submitting updates to the ledger either directly or through a payment service provider.

This would mean that almost all parties involved in traditional payments processing would be disrupted, and parties involved with processing and infrastructure will be hit hardest. If you can simply update the CBDC ledger, then traditional payment encryption, AS2805 messaging and payment routing are all made redundant.

Interestingly, parties that control the customer experience layer could emerge as important consumer access points to the CBDC. In the online world, winners could be online payment gateways like Stripe, Braintree and eWay. And in the in-store world, it could be existing digital wallets. PayPal is an obvious contender, but I think the winner will be whichever app has the most ubiquity amongst consumers. I’m putting my money on Apple Pay and Google Pay.

And if my napkin math is correct, then these companies should be able to charge consumers a CBDC ‘transaction fee’ that both supports their business model and undercuts existing payment options like cards. The key here is that cost of goods sold is significantly lower with the CBDC (i.e. no interchange and scheme fees).

Banks’ merchant acquiring business models break down

What is a bank’s merchant acquiring business in a CBDC word? The whole concept of holding a card, tapping it on an eftpos terminal, the customer walking away with their items, and the funds landing in a settlement account could completely disappear.

In fact, with ubiquitous real-time access to the CBDC, the in-store payments experience could be flipped on its head. First of all, as a merchant, you wouldn’t need an eftpos terminal or even a banking relationship. The payment experience could be driven by the point-of-sale software or merchant’s smart device, and then confirmed on the consumer’s smart device.

Bank’s probably won’t fear the loss of merchant acquiring revenue (i.e. credit card fees), as it’s a very small revenue driver. But they will fear the lost merchant relationship.

Back at Westpac, Bain & Co looked into our acquiring business. Their merchant survey revealed that 69% of merchants consider their main bank to be the bank at which they have their payments and transaction banking relationship. Those businesses are prime candidates to cross-sell lending, deposits and wealth products — all of which are at risk in a CBDC world.

Secondly, banks make ~4-5x as much revenue from deposits products that are attached to payments products, compared to direct acquiring fees. In a CBDC world, where merchant deposits do not sit on commercial banks’ balance sheets and there is no settlement, that revenue disappears.

Banks will have to incentivise customers to hold funds with them by raising interest rates on deposits. About 60% of Australian bank funding comes from deposits, so they will certainly feel the sting in their net interest margin. This is particularly painful in today’s low interest rate environment.

So with no interest rate spread available to banks for CBDC funds, competitive pressures on deposits, lower acquiring revenue and lower interchange fees on the issuing side, banks will need to seriously rethink some of their core business models.

So what now?

Sweden, Canada and China are charging full steam ahead with their retail CBDC development. And in parallel, payments players such as Mastercard are responding aggressively and trying to shape the development of CBDCs in their favour.

It’s difficult to imagine a world in which there are some advanced economies with a CBDC and others without. So, barring any major technology or risk complications, I’d expect momentum to continue for CBDCs across the globe — even for cautiously sceptical central banks like the Reserve Bank of Australia.

No matter what happens in Australia, it’ll be interesting to see what happens to incumbent banks and payment companies in CBDC geographies.

For me? Maybe another blog to unravel some of the interesting use-cases for a CBDC in Australia. For example, smart contracts that trigger payments when business logic has been satisfied. I’m looking at you, mortgages. I can’t believe I still pay with a personal cheque.

If you liked this article, drop your email in the subscription form down below. I don’t exactly write regularly — but it guarantees that you’ll be notified when I do.